To reflect on Chang’s text without exploring its use of magical realism would be deeply remiss.

But burial is beginning: To grow anything, you must first dig a grave for its seed.” It is in these moments of thoughtful symbolism that Chang’s prose shines: Each image is intentional, and even the most radical literary choices make sense.

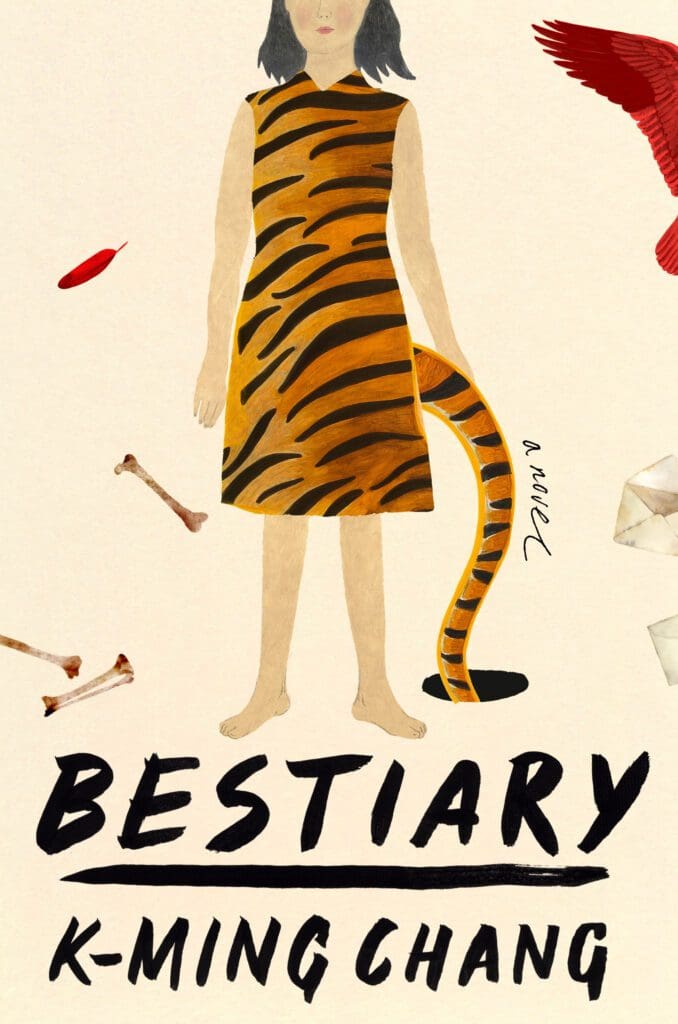

As the speaker’s mother “Ma” admonishes, “You think burial is about finalizing what’s died. They also serve as sites of both burial and birth. The holes in Chang’s narrative demonstrate the obscure ways in which life twists on itself, taking in the ordinary and spitting out the extraordinary. Both convey a sense of profound emptiness that exemplifies the speaker’s interior restlessness. Two themes cohere Chang’s story: hunger and holes. An inward-facing, temporally non-linear narrative, Chang’s prose moves freely from past to present, daughter to mother, China to America to provide a sweeping, detailed portrayal of the psychic complexities of migration, loss, and love. From this collective - and largely futile - search for treasure emerges motifs of burial, reinvention, memory, and dispossession that serve as key threads in the novel’s broader textual fabric. The breathing, mythic holes in the speaker’s backyard conceal flashes of skin and scraps of words, serving as a dynamic intermediary between the speaker and her estranged ancestral past.Ĭhang’s story opens with her unnamed speaker recounting her family’s search for lost gold. A father and son, enmeshed in an abusive relationship, ascend to the sky like kites and tussle in the wind. The speaker’s tiger tail, which begins to grow as she enters puberty, expands into an embodiment of protection, female sexuality, and matrilineal inheritance.

In K-Ming Chang’s debut novel “Bestiary,” characters are defined not by their given names but by their surreal, otherworldly qualities. There is an intimate universality reserved for stories with nameless characters.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)